What Galaxies Remember and Other Space Miracles

How we interpret natural wonders that the mind can't grasp

Last week, NASA announced the discovery of the most distant star ever detected. Astronomers called it Earendel, or morning star in old English because it was born just after the dawn of our universe, about 900 million years after the Big Bang.

This star is bigger, older, and farther from us than the mind can grasp. Light from Earendel travels about 12.9 billion light-years to reach Earth. And it is, or was, a massive body, 50 to 100 times larger than our sun and millions of times brighter.

Those numbers are hard to process because our perceptions of scale are constrained by the dimensions of our own experience, whether we're trying to imagine the size of a galaxy or the intensity of another person's loss. As Italian-Jewish author and chemist Primo Levi put it:

"For a discussion of stars, our language is inadequate and seems laughable, as if someone were trying to plow with a feather. It's a language that was born with us, suitable for describing objects more or less as large and as long-lasting as we are; it has our dimensions, it's human."

Now we have artificial intelligence to calculate what we can't imagine. Using a machine learning algorithm, scientists can examine a single galaxy and predict the composition of the universe in which it lives. It's akin to estimating the mass of our largest continent by analyzing a grain of sand or mapping the parameters of a giant forest by examining a single tree.

A co-author of this work, theoretical astrophysicist Francisco Villaescusa-Navarro described this research to the New Yorker lyrically (another reminder that scientists are often poets, too): "It does look like galaxies somehow retain a memory of the entire universe."

What a magical concept. But it's possible we like the suggestion that galaxies remember where they came from because it sounds so... human. Inherited memories and origin stories passed down through the centuries are central to our identity.

Twentieth-century American writer Joseph Campbell talked about a "monomyth," the idea of a hero's journey that persists across generations and cultures. A common dream. Among Aboriginal people, Dreamtime is the story of the universe, a beginning without end, a point on a continuum of past, present, and future. And, 18th-century British poet William Blake said it simply:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

Perhaps the algorithms aren't so different from our humble minds. You don't need theoretical physics to explain how decades-long love can be compressed into a single gesture that contains everything that has ever been between two people—wordless comprehension in a millisecond.

When confronted with immeasurable kindness or cruelty, we look for singular stories–a universe of grief and triumph bound into a single image or moment. These are small understandable units of a vast, more complex whole.

I’m reminded of an indelible photo of a young Ukrainian mother who physically shielded her weeks-old baby girl as shrapnel flew. She is transfixing, this bandaged woman now safely in a hospital bed, face speckled with cuts from the debris of her city, shoulders bare, holding her newborn.

I thought I could see the scale of a nation's suffering in her eyes. However, our interpretations are a kind of mirage. We superimpose our own story on that mother, using the filter of our own memories to translate the terror we see in her face. We can recognize our parents or our children in the fierce way she presses her newborn against her chest. And in her survival, we measure our own good fortune. Such is the mercurial science of the heart.

We find what we ache to see. We discover villains and heroes when we need them to clarify something complex and overwhelming. Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy became the figure his people needed and perhaps what the world needed. Was this former comedian always made of such strong stuff? Or was he forged in the fusion of a moment—a deadly threat plus a collective prayer for leadership?

Joseph Campbell might have said that our view of Zelenskyy is shaped by the hero's journey myth we carry within us. But it's a cautionary tale; mortals can rarely sustain the weight of myth for long.

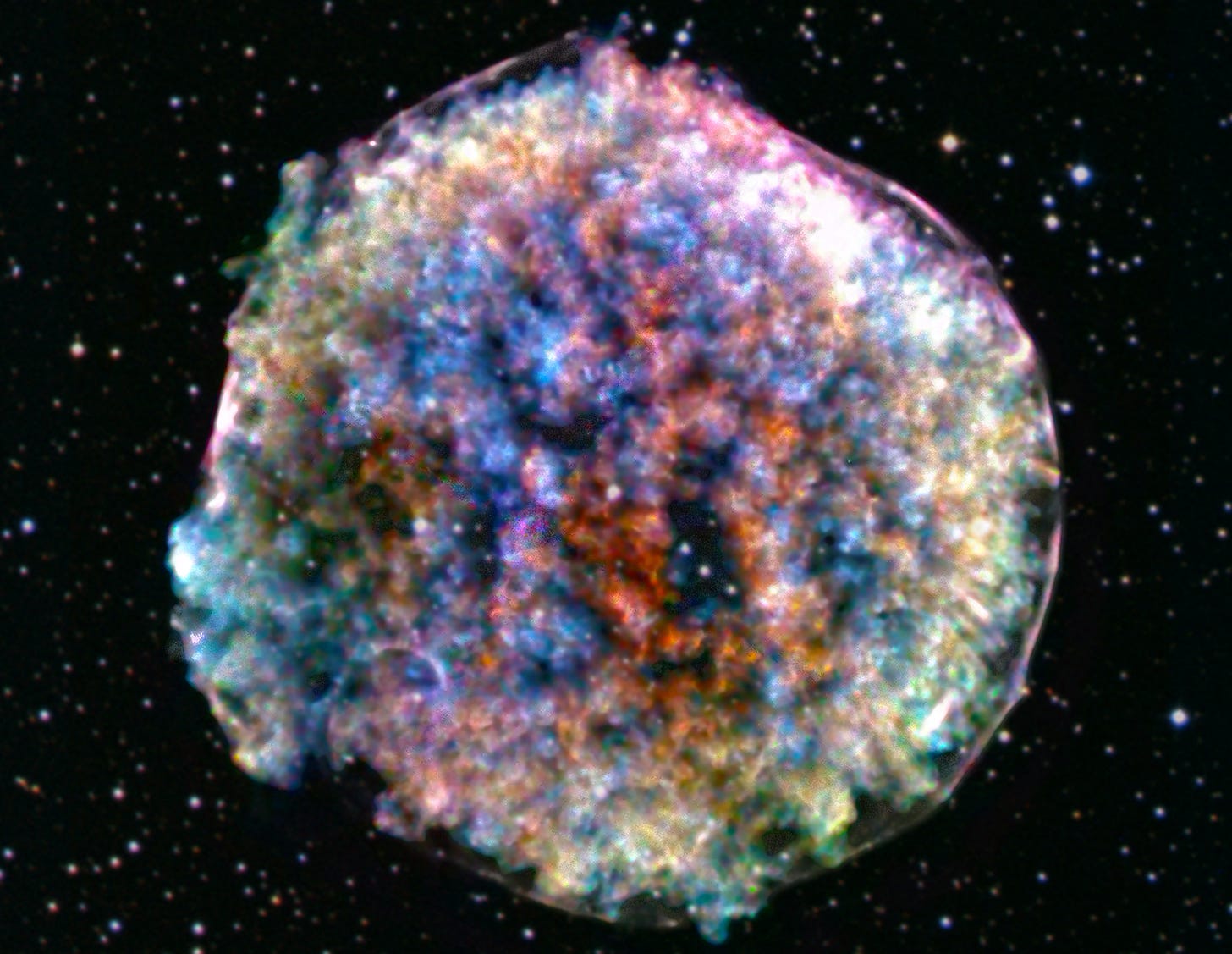

Researchers also caveat their findings accounting for the limits of their interpretation. Some of what they see is also a mirage. With the Earendel discovery, they reminded us that the picture they're getting via the Hubble telescope may have gotten distorted on its long road to us. Earendel may not even be one spectacular star, but rather three, with one outshining the rest. And it is likely a cosmic ghost. What we perceive might be light from a star that's now a black hole after succumbing to the gravitational pull of its own weight. And what a brilliant light it must have been. When massive stars like this die, they create a supernova, the brightest, most spectacular explosion we know.

For most of us, what we see in the stars is as much an extension of our own myths and hopes as a measurable reality. When I see news about those wise old stars, I think of them as messengers from the beginning of the beginning, a reminder that light can outlive its maker. And those poet/scientists over at the Hubble Space Telescope's Twitter describe glimpsing Earendel as like "looking at a very old photo of a young person who lived a long time ago, or hearing the oldest recording of a singer who is long gone."

It’s Not Just You is a free weekly essay, uplifting recommendations, and a community of thousands. If you love it, consider supporting my work with a paid subscription. You’ll gain access to “Dear You,” a monthly advice column and special podcast editions.

Send your advice questions by replying to this email or submitting one here.

This “Solar System,” quilt was made by Ellen Harding Baker (1847-1886), an American astronomer and teacher. It came to the National Museum of American History in 1983, a gift from her granddaughters.

Margaret Atwood on Feelings: “At least [author Christopher Hitchens] didn’t accuse me of hurting his feelings, nor did I accuse him of hurting mine. Having feelings was not a thing back then. We would not have admitted to owning such marshmallow-like appendages, and if we did have any feelings, we’d have considered them irrelevant as arguments. Feelings are real—people do have them, I have observed—and they can certainly be plausible explanations for all kinds of behavior. But they are not excuses or justifications.”

—From Atwood’s acceptance speech upon being awarded the sixth annual Hitchens Prize last week.

Well hello! I’m so glad to have you. If you love It’s Not Just You, please share it or consider upgrading to paid subscription.

“ I was much older when I was 20 than I am now.” This interview with Jane Fonda about the 40th anniversary of her iconic workout tapes is priceless.

How Can Individual People Most Help Ukraine? Anything helps—we shouldn’t overthink it. But we should still, well, think it By Joe Pinsker

More: Find me on Instagram here: @susannaschrobs

Need advice? Write to Dear Suze here, or reply to this email. Here’s last month’s column:

Such a beautiful, poetic piece! What is that saying about having "the stars in our eyes"?!

What a miracle it is, given the history of space/time and the incredible collection of atoms that we are, that I am here to say thank you for your post to a you that is here, as well