Maybe the Kids Are More Resilient Than We Think

Plus a few escapist delights.

Well hello! I’m so glad to have you. If you love It’s Not Just You, please share it. (More about me and this newsletter here.)

A baby's skull is so soft and malleable that there's a little gap at the crown that allows the human brain to grow exponentially in the first three months of life. It's one of the most fragile moments in development, yet there's such resilience too. If a newborn's head is compressed during birth, its contours can be reshaped gently over time.

The first parental commandment is, of course, to support and protect that little head—it contains all that is possible and all that is necessary. If you think too long about the scope of that responsibility, it's paralyzing.

I remember standing on the steep steps of a brownstone in Brooklyn holding my newborn child, just four weeks in the world, when a sharp March wind unexpectedly rushed up from the Hudson River. I thought the baby would be swept out of my arms like in a fairy tale. I was afraid to step down the stairs, afraid to stay at the top, afraid to move one hand from the baby to hold onto the railing. It was irrational, and I knew it.

For weeks in the hallucinogenic hours between night feedings, I dreamt that the baby really had been pulled into the sky above the painted scrollwork of the old buildings. I could see her blanket unraveling and her striped hat blow away, exposing a downy scalp and the strange mullet-fringe of newborn hair at the base of her neck. The wind carried her up safely past the chimneys, cables, and pipes that poke out from the rooftops.

Last December, I was reminded of those old anxieties when a lethal tornado crashed through Kentucky. A 3-month-old and his 15-month-old sister were found bruised but alive under an overturned bathtub. Their grandmother had tucked them in there before her house was leveled. "Next thing I knew, the tub had lifted, and it was out of my hands," said the grandmother. "I couldn't hold on."

No one would say those children were more resilient for having been thrown into such deadly chaos. If it were your child, you'd watch her for years to ensure there was no invisible damage. But we watch like that even when there's no storm. We stare at the tender faces of our babies like insecure yet ambitious gods of a small universe. We think we run the place, but we really don’t. All we can do is wonder what they absorb from their surroundings, from us, and from our mistakes.

And then we pad our houses and our speech trying to give them joy without loss, excitement without risk, confidence without hubris, love without pain. In essence, we try to create a world for those children that is nothing like the one they'll grow into.

At what age do you ready them for the ugliness that will someday visit them directly or indirectly? Do you prepare them best by being tougher earlier, allowing them to feel the brunt of their failings and yours? Does exposure to the world's realities and traumas stoke resilience, or does it rub them so raw that everything hurts them all the time?

My two kids are mostly grown now, and I still don't know the answer.

Heck, I'm not even sure what constitutes trauma in this era when we live in some ambiguous space between enlightened self-reflection and Munchausen by Tiktok. As Jessica Bennett put it in The New York Times this week, "If Everything Is ‘Trauma,’ Is Anything?” The language of psychological damage is now so common that it threatens to compress all our hurts, both deep and temporal, into single definitions that are stretched beyond usefulness.

I think we'll have to find new language for the travails coming our way in the next few years. We were already talking about trauma and burnout before the pandemic, and it was not easy to articulate the next-level stress that came with that particular isolation and loss.

And none of this tells us whether our kids are prepared for the storms they'll face as adults. They are fierce about their expectations and in their outrage at the slowness of change. And yet still soft enough that every hurt is visible. But I think about the teenagers who lived through the Blitz in London during World War II with bombings, rations, and nights without light or guideposts. Their parents had no precedent; they couldn't have prepared their children for that.

Maybe the only choice then and now is to give ourselves over to hope, and to believe that some innate human resilience and youthful adaptability will kick in and that they’ll find their way to safe ground. Though that doesn't mean that mothers will stop questioning their decisions and dreaming of babies flying into the night.

It’s Not Just You is a free weekly essay, uplifting recommendations, and a community of thousands. If you love it, consider supporting my work with a paid subscription. You’ll gain access to “Dear You,” a monthly advice column (launching later this week)and special podcast editions.

DELIGHTFUL STATES OF MIND

On ‘Asset Framing’ and the Stories We Tell Ourselves: Krista Tippett , host of the On Being podcast talks with Trabian Shorters, an author and former tech engineer who developed a healing technique called "asset framing." Rooted in our understandings of the brain and the real-world power of the words we use, the stories we tell, and the way we name things and people. We have a habit of seeing deficits — and defining people in terms of their problems. Shorters argues it's time to change that.

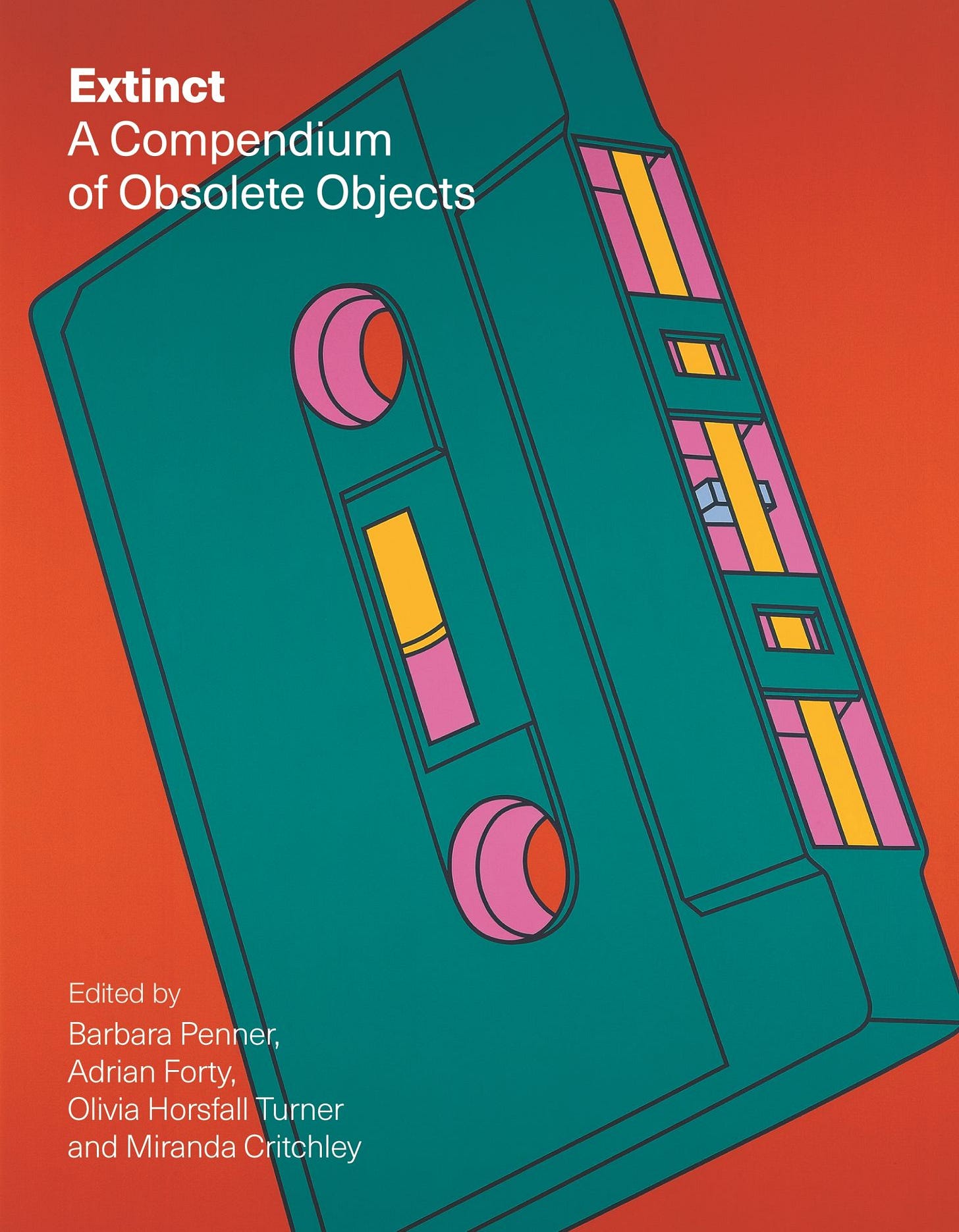

In Extinct: A Compendium of Obsolete Objects, contributors nominate eighty-five “extinct” objects and address them in a series of short, vivid, sometimes personal essays, speaking not only of obsolete technologies, but of other ways of thinking, making, and interacting with the world. There's "something illicit about possessing an ashtray, associated as it is with the mild rebellion of smoking cigarettes," writes The Baffler.

ESCAPIST DELIGHT

Via @VogueFrance Instagram: And just like that… Carrie Bradshaw came back to Paris, and her trip was worth wearing @MaisonValentino couture for! (on the Pont des Arts). Say what you will about the “Sex and the City” reboot, the fashion was a treat.

POETIC DELIGHT

It’s a good week to watch Mary Oliver read "Wild Geese" and be reminded that you don’t have to be good to be good enough to take your place in the family of things.

Wild Geese

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

For a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

Share thoughts about your favorite obsolete items, resilience or whatever’s happening in your world in the comments. And anonymously submit your advice questions here.

I loved this article so much! I think we mothers can all relate. I can remember holding my first baby trying to get him to stop crying. I was feeling frustrated and I started just picturing throwing him down the stairs (I know that sounds horrible!), but just going through how I would feel IF I really did that, calmed me down and gave me patience to continue trying to soothe him.

For the obsolete--I miss milk boxes and the milkman. I recently learned that my farm dairy, that we all knew and loved was sold several years ago and the land is now becoming a housing development. :-( It is such a happy memory for me to remember getting the milk out of the milkbox (in bottles!) and if we needed extra for company, all we had to do was put a note out and he would leave more. Such simpler times!

Another essay that pulls back the covers on the heart.

I think kids develop resilience by being allowed to have the bumps that come naturally, without being (overly) protected. Give a child a safe place to bring fears and hurts, but don't prevent them.

Parents need deep insight and good judgment to know what bumps are ok and what needs shielding. Mostly, I think, we need to know what our kids can handle and where their resilience stops.

Talk about tall orders.