On Becoming an American Immigrant and the French Visa Medical Exam

Oh, the peculiar joys of universal health

Well hello! Here I am in your mailbox with a story of acceptance and immigration. Also, if you’re a writer who likes the idea of writing in Paris, check out this workshop I’m co-hosting in April, The Blue Hour.

In my family, we are either becoming immigrants or marrying them. I come from two lines of northern Europeans prone to moving three or six thousand miles East or West, and not just once in a lifetime. We go from Russia to California and points in between. We leave for love, or because of war, or, like me, to become new again.

I don’t know if this means my people enjoy not fitting in or that they are good at fitting in anywhere. Maybe both. But here I am in Paris, an immigrant again with that dueling sense of precariousness and gratitude that comes with not being a citizen.

This kind of transplantation involves paperwork. But at least the bureaucratic language in France sounds fancy and dramatic. It entertains me to no end. For example, I got a “convocation” with a date for my official French medical exam to validate my visa. A convocation! How thrilling. Sounds like a graduation ceremony for when you reach a new level of immigration.

Not until I was in on the Metro to get my exam did it occur to me that I could perhaps fail this test and be sent back to the U.S. And who knows what would be disqualifying? What if I’m riddled with the bad type of cholesterol, or they discover I have a disease I’ve never heard of?

When my Irish and Swedish great-grandparents arrived at New York’s Ellis Island, American health inspectors would lift immigrant eyelids with a button hook to see if they were sick. Anyone who appeared to have a “Class A loathsome or dangerous” disease or seemed mentally unstable had their coats marked with a chalk symbol, like S for senile. They were then pulled from the line and sent to wait in pens for further examination. Those sturdy housemaids and carpenters who had come so ridiculously far by ship must have been terrified of being turned away.

And now, 100 years later, I’m one of a whole bunch of Americans wanting to go back in Europe, hoping we’ll be accepted. Oh, the ping-ponging irony of it all.

When I checked in for my convocation at a big building just south of Paris, they handed me a six-page psychological questionnaire and directed me to a central waiting area. It was a large room surrounded by a series of doors on three sides. So very many doors, some with pictograms — one looked like a scale, and another had a radioactive warning. I watched people go into one door and come out another, with doctors popping out like gophers to direct us. It reminds me of the British play Noises Off in which actors slam doors in and out of scenes with perfect comedic choreography. I suspect that the entire French public health system is based on a startlingly efficient set of doors that move patients through a series of interlocking changing rooms that open into exam rooms or back into the waiting room.

I leaped up when one of the doctors seemed to say something like SCHROBSDORFF while pointing to a door to his right, then disappeared behind his door. So, like Alice in Universal Healthcare Wonderland, I entered what turned out to be a room smaller than a toilet stall. There were two hooks, a bench, and a second door that didn’t have a handle on my side. There was no gown to change into, which would be unheard of in the U.S., nor were there written instructions. What to do? Get fully undressed? Wait for further instructions via a hidden speaker?

It’s entirely possible this was a cognitive test.

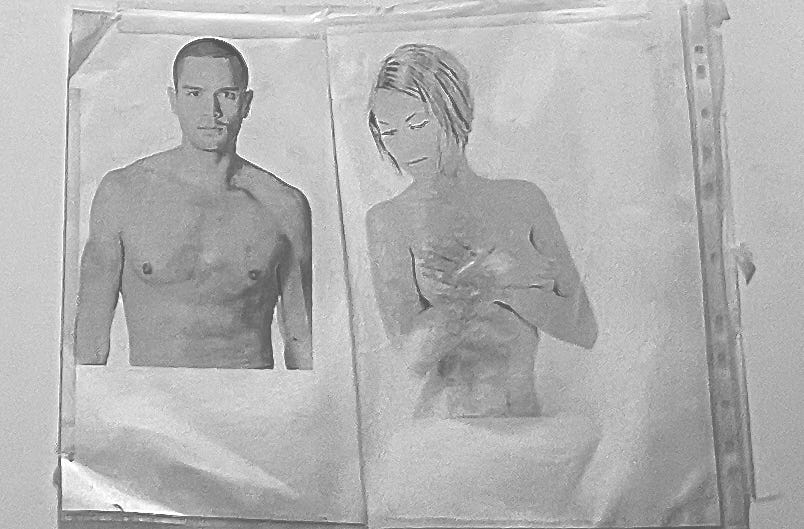

But wait, on the wall in the corner there were two much-Xeroxed images of a 90s-looking couple topless. So, in the spirit of doing as the French do, I decided to make like the lady in the picture. I took off my top and sat on the bench, arms crossed. I was very demure, very mindful, and very worried that one door or another would open, revealing me to a waiting room full of people. Finally, an unseen someone on the other side of the handleless door cracked it just a few inches. A signal! I could see an X-ray machine on the other side, so I stood up and walked right out there gownless, chin up, tits up (sort of), and left American modesty behind.

And so it went. They moved me through door after door, did every conceivable test, weighed me and recorded my height in one room, and tested me for diabetes and HIV with a finger prick in another room. Just a “petit pain,” said that doctor. It was like being the car in a car wash. Yet I was reliably befuddled throughout, forgetting how to get on a scale or unable to find the exit of a space I’d just walked into. The Ellis Island inspectors would have marked me with an S. But in my defense, something about losing cultural context turns you into an idiot.

Most of the people with me in the waiting room were from China. I know this because I heard the French doctors greet them with a hello in Chinese. (My, how things have changed!) But there was one other American. I heard her chirp BONjour with a booming American accent. Her hair was satiny, blow-dried highlighted blonde, and she wore a black dress dress shirt, collar up.

That BONjour! She’s so American. So unlike me, I thought. Not two minutes later, a doctor confuses us, calling her Schrobsdorff. As she enters the X-ray door, I realize I own the same black and white Hoka sneakers she’s wearing. Generic American lady of a certain age who loves Paris, c’est moi. I’ll always be that here. It’s the bargain you strike when you leave home. According to the expat gods, you will be humbled and seen through the filter of national cliches.

Just before I got to the last door, the one with the pictogram of a doctor consultation, I started to look at the psych questions. Some were a paragraph long in French and exceedingly personal. They included this:

“Have you had a period during which you spent a lot of time being afraid of gaining weight or becoming fat or trying to control your food intake?” OUI ou NON?

First of all, bahahahahahah! But more importantly, which answer would make France accept me? Because I am, after all, just a girl standing in front of a new country asking it to love me. Maybe I circle NON because, in truth, there was no single period of time when I feared gaining weight. It’s been pretty much every day since puberty. But maybe I should answer OUI because a healthy fear of weight gain might be a plus if you’re coming from America.

There were at least four questions about alcohol and drug consumption, including whether I’d ever consumed it to calm anxiety. Or at least, I think that’s what they were asking. I was too proud to ask for the English version, which is also the reason I keep accidentally ordering kidneys in restaurants.

The last doctor had my chest X-ray on the screen when I walked in, which was unnerving. I thought we were about to have a difficult conversation. But it was fine. She was offering to take a picture of it with my camera so I would have a record of my healthy lungs. Something nice to post on a dating site for seniors.

She and I spoke in French till we both realized that it's a second language for both of us, and we laughed. Above her mask, I see her eyes are that cornflower blue I associate with the Ukrainians I met in Odesa on a reporting trip back when they first declared independence from the former Soviet Union—another bit of rhyming history. And indeed, she’s from Ukraine, where she was a pediatrician. We talk about how gorgeous Ukraine is, how much she misses her old practice, her country, and her peace of mind.

She's a reluctant immigrant whose country seems to be getting further out of reach every day. She can’t go home, and I don’t want to go home. I have the privilege of choice, she doesn’t. Yet, there we are, united in our not-Frenchness, cracking up over the specificity of those psych questions. I joked with her about one that I read as: “Have you heard voices in your head that are not your own.” I told her I feel lucky when I do. The doctor nodded like I was making sense. Lately, I hear the voice of my fearsome grandmother, Anja, who fled pogroms in St. Petersburg. She lived in Montparnasse in the 1920s with other Russian Jewish expat artists and writers and went on to three other countries after that.

An hour and a half after my convocation began (what efficiency!), they handed me a gorgeously official, stamped letter stating that the French government had approved me and my health. I’m thinking of framing it like a diploma. To get the Metro home, I had to pass a massive Kentucky Fried Chicken outlet. Proof that you can run, but you can’t hide from America.

RELATED:

Driving To Odesa On a Very Warm September Day

One very warm September, a few years after the Soviet Union fell apart, I took a cab from Kyiv seven hours south to Odesa. It is and was a glorious city that sits on the north side of the Black Sea like a grande dame.

I thoroughly enjoyed this, laughing so loudly at one point that I scared the dog.

I loved reading this and actually laughed out loud during some parts!

I did my health exam almost two years ago and I relate to so much of this. I am relieved after reading the part about you stumbling in the doctor’s office, becoming somewhat of an idiot, because I suffer from making mistakes in the most mundane situations. Roaming around like a clumsy toddler. It made me feel a little less broken!

Also like you, I fit into a cliché. I’m of the “American woman with brown hair and bangs who dresses a little weird, so she must be exactly like Emily in Paris” kind. I have to remind French people who call me Emily that Emily didn’t bother speaking French, and I am not trying to be an embarrassment here! 😂